AUTHOR’S NOTE

What follows is the story of two outsiders whose lives intersected in and around Paris in the dark, desperate years before the Second World War.

Both were foreigners in France, having gone there to escape their pasts and secure their futures. Both adapted quickly to their new surroundings, helped by their ability to seduce strangers in several languages, by their physical grace and magnetism, and by their shared gift for paying attention. Both longed for beauty and sought transcendence through great works of music and literature.

One was a journalist, a representative of American self-invention, American wit, and American love for democracy, who discovered that she did her best work outside of America. The other was a German confidence man and killer, a man so misshapen that when the Nazis occupied Paris they tried to destroy all record of his crimes to avoid being tainted by association.

By telling the stories of these two outsiders in tandem, I hope to capture both the brutality of the era in which their lives briefly touched and the strength people summoned to survive it, as they fought to maintain some measure of civility while watching civilization fold in on itself. (Pg.ix)

THE LAST PUBLIC EXECUTION IN FRANCE

Versailles, June 16–17, 1939

(Pg.1)

A woman tried to slip behind the police cordon to take her place among the 160 invited guests who stood in a semicircle a dozen feet from the guillotine. She’d disguised herself as a man, as no woman, aside from the German’s favorite lawyer, had been invited into this inner sanctum of spectators. She was found and arrested.

Another woman, immaculately dressed, approached the cemetery official charged with transporting the body. She pushed a handful of bills into his hands. She wanted to buy the dead man’s head. She was also arrested.

The Monsieur de Paris ducked into the prison to tell the warden they would have to push things back an hour. Rather than in darkness, as planned, the event would take place in the light of dawn.

The German changed from his prison uniform into dark blue pants and a white shirt. A guard cut his long hair and with the same scissors sliced off the top of his garment, exposing his broad chest and shoulders, pale from confinement. Such precautions ensured that the blade would make a clean cut.

A telegram arrived from New York and a translator had to be found, adding further delay. The parents of one of the victims wanted to know if before strangling her the German had raped their daughter. “No,” he said. “I didn’t touch her.”

He took communion. He refused the customary cigarette and shot of rum. He signed some documents: He had to be officially released from the prison before he could be killed outside its walls. After signing for his freedom he was bound from head to toe. His favorite lawyer removed her gloves and touched him on the shoulder.

Two of the executioner’s assistants led him out the heavy green doors. His final sights would be of a few police vans; some thin trees; a horse roped to a flatbed; a newsstand; an ornately curved streetlamp, unlit; soldiers manning some low temporary fences against the shaking crowd; the half ring of invited spectators; and the executioner and his accomplices wearing dark suits and fedoras, looking like bankers pulled from their offices to perform this somber task.

He buckled when they pushed him toward the guillotine and then shut his eyes and kept them shut. His favorite lawyer shut her eyes, too, but a senior colleague told her to keep them open. She bit her lip hard to keep from fainting.

He’d been so tightly bound he could walk only in short paces. When they laid him down, his head facing the ground, his hands behind his back, he jerked against his constraints, once, before going limp. The executioner judged the blade to be misaligned. Instead of taking the time to readjust the blade, he told an assistant to reposition the head to a more favorable angle, which the man did by pulling it toward him by the ears. The German shook loose and the assistant repositioned him again, grabbing him now by the hair. The executioner pulled the cord release. It was four thirty-two in the morning.

From the apartment’s roof they pelted the parked police van with champagne corks. Nearby, officers loaded the body into another of the vans, which sped off for the cemetery, though not before the dead man’s favorite lawyer had glimpsed her client’s bloodied head in the basket.

Guards splashed the sidewalks with buckets of water as a few women dipped the hems of their dresses in the red, believers in the centuries-old myth that a condemned man’s blood increased fertility. The spent guillotine was disassembled and carted away. (Pg.5)

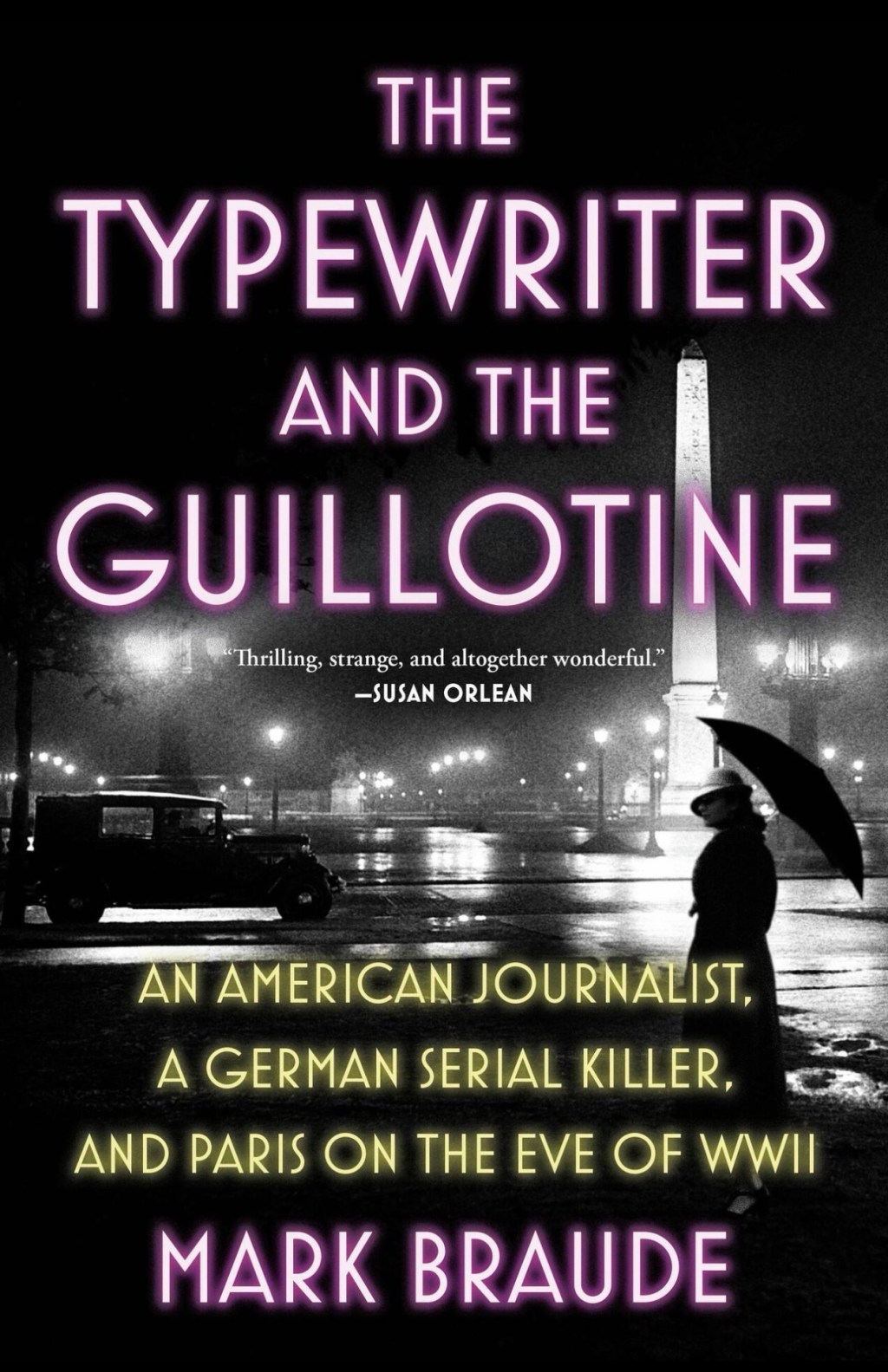

“The Typewriter and the Guillotine: An American Journalist, a German Serial Killer, and Paris on the Eve of WWII” by Mark Braude