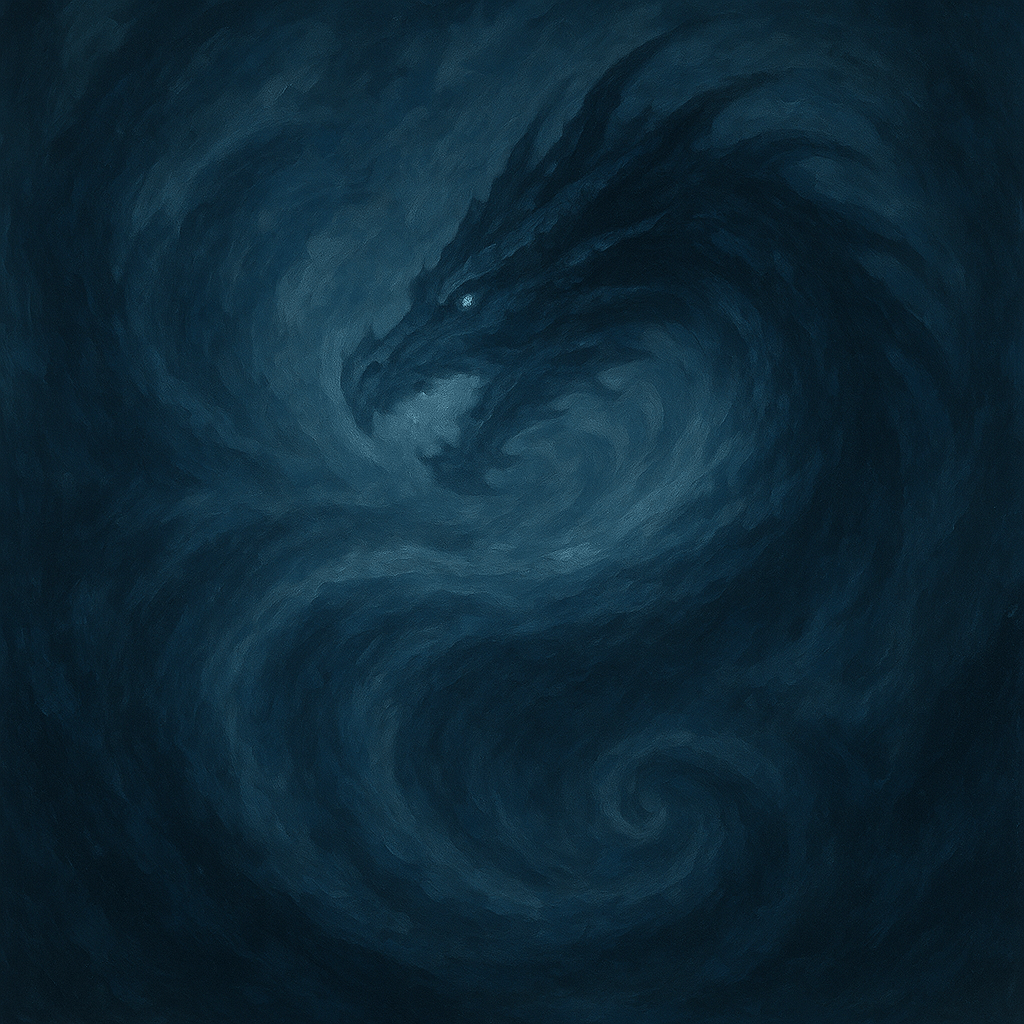

Europe: the dragon as chaos to be slain

In medieval Christian Europe, dragons often embodied evil, chaos, paganism, or the forces resisting salvation. The tale of Saint George and the Dragon has him slaying a beast terrorizing villagers, offering both a moral and political reading: the hero (often Christian) overcomes disorder. (Holyart)

Later artists and chroniclers layered in symbolism of righteous kingship, sanctified warfare, and conversion. (Art and Object)

China & East Asia: benevolent sovereign of rain and power

In contrast, the Chinese dragon (lóng / long) is not to be slain — it is revered. It is deeply associated with water, weather, and cosmic balance. (Wikipedia)

The dragon is a symbol of imperial authority: emperors claimed dragon symbolism (robes, palaces) to underscore their mandate. (Wikipedia)

There are divine or semi‑divine dragon kings (lords of seas and rainfall) who regulate rain, rivers, and floods. (Wikipedia)

One example is Shenlong, the spirit dragon of storms and rain. (Wikipedia)

Another: Yinglong, a winged dragon in ancient myth, linked to rainmaking and responding to human ritual. (Wikipedia)

Mesoamerica: the Feathered Serpent as creator‑ruler

Quetzalcóatl (“feathered serpent”) marries the serpent (earth, fertility, water) with bird imagery (air, wind). (Dragons)

He is often cast as a civilizing deity: bringing maize, knowledge, rulership, sometimes the wind itself. (LinkedIn)

Unlike European dragons, Quetzalcóatl is rarely a monster to vanquish — he is more akin to a patron or ancestral force.

Bridge to modern resonance: “House of the Dragon” (2024)

In House of the Dragon Season 2, dragons remain literal and symbolic: weapons of war, embodiments of dynastic legitimacy, and volatile forces that must be managed, not simply destroyed. (Collider)

The Targaryen sigil—three‑headed dragon—surfaces repeatedly as a visual anchor of legitimacy and fracturing house identity. (Medium)

Dragon names, their color and temperament, and their allegiance mirror political fault lines. (YouTube)

Why this matters

Across time and place, dragons aren’t just compelling fantasies — they map to authority, legitimacy, and elemental forces (water, storms, fertility, war).

- In Europe, the dragon is external evil to be vanquished as a metaphor for political or spiritual dominion.

- In East Asia, the dragon is internal to sovereignty — it’s a force to harness or personify rather than destroy.

- In Mesoamerica, the serpent‑dragon spans mortal and divine domains: rulership, cultivation, cosmic renewal.

- In HOTD, dragons revive these tensions: they are tools of rulership, but dangerously autonomous.

Closing Reflection: The Dragon’s Breath in Us

From Europe’s saints to China’s emperors and Mesoamerica’s sky serpents, the dragon remains a mirror for how humanity imagines its own power. Each culture, in its own idiom, speaks of control—of the storm, of the self, of the cosmos. Whether slain, worshipped, or befriended, the dragon embodies that uneasy balance between fear and reverence, chaos and order.

Modern storytellers like those behind House of the Dragon inherit this mythic grammar but turn it inward. The question is no longer only who controls the beast, but who becomes it. The dragon is lineage, ambition, grief, and the fire that both warms and consumes.

To look at these myths side by side is to see an evolution of moral geometry: from external conquest to internal reckoning. The dragon now lives within us—as creativity, rage, vitality, or transcendence. And whether in scripture, sky, or screen, its wings still cast a shadow over every throne, reminding us that power, like fire, demands both awe and humility.

WE&P by: EZorrillaMc.

You must be logged in to post a comment.