The Empty Chair: Mindful, Not Fearful

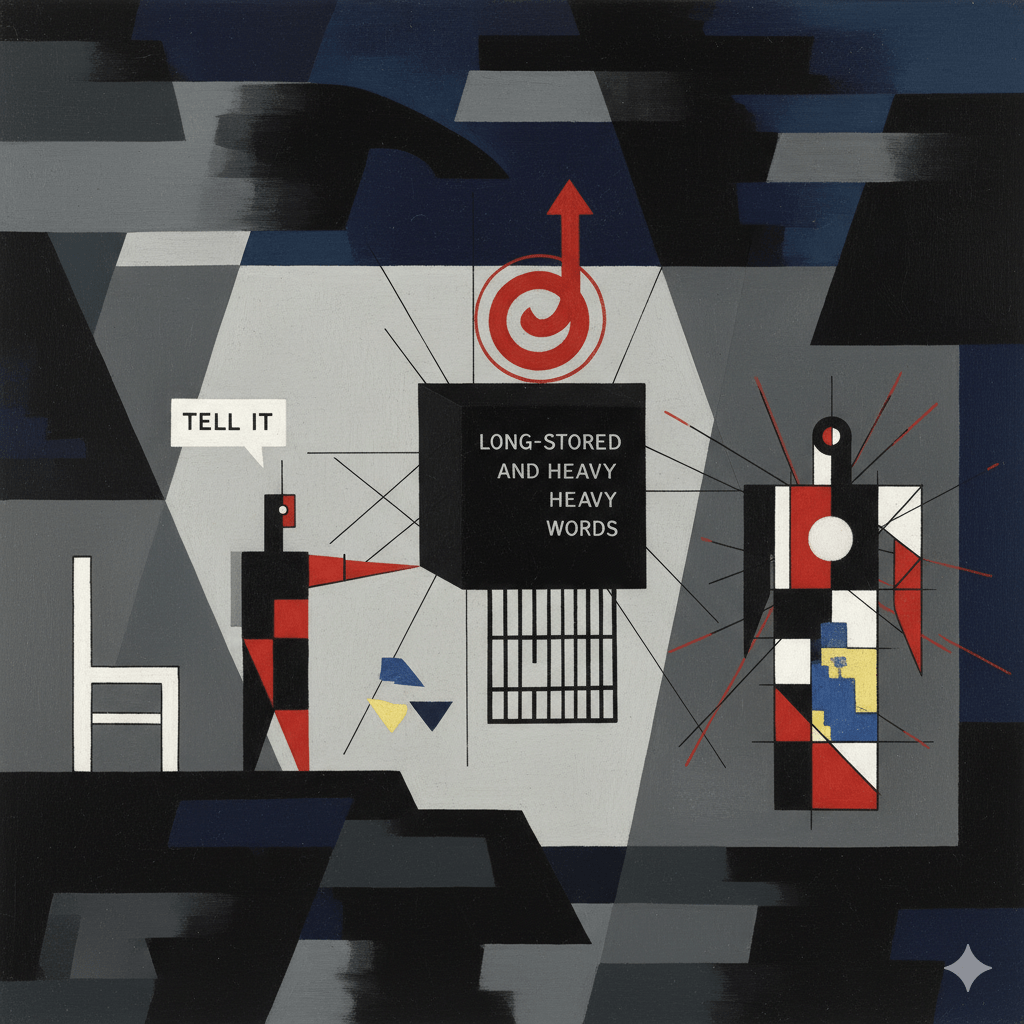

There’s a particular quiet that settles just before you speak—the kind that feels like standing on the edge of a cliff, wind pressing against your back. You can sense the words rising, long-stored and heavy, and yet you hesitate. Silence has been your shelter and your cage. Then someone gestures toward the empty chair across from you and says softly, “Tell it.”

It sounds foolish. But absurdity is sometimes the first language of healing.

So you speak. Not for them to hear, but for you to release.

The room doesn’t change—but you do.

1. The Voice That Names

Gestalt therapy begins here, in the simple act of naming. It’s not analysis; it’s expression. You don’t dissect the feeling; you voice it until it recognizes itself. The “empty chair” isn’t really empty—it’s the space where all unspoken words have been waiting. When you finally fill it, you learn the oldest truth of healing: the issue was never them hearing you—it was you expressing it.

James Pennebaker wrote that turning emotion into language transforms the nervous system itself. The words rewire the body’s stress circuits, like clearing a riverbed of debris so the water can move again. What Gestalt discovered in the therapy room, Pennebaker found in writing, and Wallace turned into fiction: liberation through articulation.

To speak is to map the shape of your own imprisonment.

2. Literature as the Second Chair

David Foster Wallace understood this intuitively. His novels are full of people talking into the void—AA confessions, late-night monologues, taped interviews. These characters don’t speak to persuade; they speak to unburden. Wallace’s pages vibrate with that same therapeutic logic: truth arrives not as insight but as utterance.

Jon Baskin, in Ordinary Unhappiness, reads Wallace through this lens. For him, the writer isn’t offering answers; he’s staging encounters—moments where self-deception breaks down under its own noise. The fiction becomes a therapeutic space, a modern mirror.

Each reader, like a patient, overhears themselves. That’s why Wallace’s work feels both intimate and uncomfortable: it forces us into our own session, with no one else in the room.

In Gestalt therapy, you don’t talk about the problem—you talk to it.

In Wallace’s fiction, you don’t interpret meaning—you experience it talking back.

3. Ordinary Unhappiness

Freud once defined the goal of therapy as converting “hysterical misery into ordinary unhappiness.” It sounds bleak until you realize how humane it is. Ordinary unhappiness is what life feels like when it’s not distorted by avoidance or denial. It’s the peace of being fully awake to your limits.

That’s what Baskin finds in Wallace’s work—a movement away from the grand, self-destructive search for transcendence and toward a more honest, sustainable kind of living. Infinite Jest begins in chaos but ends, tentatively, in surrender: characters learning to sit still in their own discomfort, to endure the unglamorous work of being human.

Gestalt therapy aims for the same quiet victory. You don’t conquer pain; you integrate it.

You trade the illusion of control for the dignity of contact.

Mindful, not fearful.

4. The Expression Spiral

When Jennifer Fletcher writes about “teaching arguments,” she’s describing a civic version of this same practice. Argument, at its best, isn’t combat—it’s collaboration through expression. We talk not to win but to understand the edges of our own thinking.

Paul Theroux’s Dark Star Safari and Gregory Diehl’s Travel as Transformation extend the metaphor outward: travel as dialogue with the unfamiliar, a living conversation between inner map and outer world. The journey itself becomes an argument—a negotiation between comfort and change.

Even Ryan Duns’s Theology of Horror fits the pattern. Horror, he suggests, is the genre that makes us articulate our most repressed fears. The monster only loses power once it’s named. Whether in therapy, literature, politics, or faith, the mechanism is the same: expression as illumination.

What we cannot name, rules us.

What we speak, we start to re-own.

5. The Listening World

Masha Gessen’s The Future Is History chronicles a society that forgot how to speak its truth. Under authoritarianism, silence becomes pathology. The unsaid festers until it turns to cynicism or violence. Against that backdrop, expression itself becomes an act of resistance.

So the “empty chair” scales up—from a therapist’s office to the public square.

Societies, too, need a place to say what has been suppressed.

And when they do, it’s never elegant. It’s awkward, raw, necessary—like therapy, like democracy, like any honest conversation.

The point isn’t eloquence. The point is contact.

6. Rebuilding the Bridge

What Baskin, Wallace, and the Gestalt tradition share is a refusal to separate intellect from feeling. They insist that thinking and speaking are moral acts. The philosopher’s insight and the patient’s confession are two versions of the same human effort—to make experience bearable through form.

Stanley Cavell called this “philosophy as therapy.” Wittgenstein said, “Don’t think, look.” Gestalt adds, “Don’t analyze, express.” Together they form a triad of modern mindfulness: awareness, articulation, integration.

In each, the task is not to escape suffering but to inhabit it more honestly.

Not to fix, but to face.

Not to silence, but to voice.

This is how expression becomes ethics.

7. Closure Without Finality

When the session ends, the chair remains. Empty again, but changed.

It has absorbed your history like a quiet witness.

The words have left your body, and in their place is air—space enough for the next breath, the next beginning.

You step outside. The world sounds slightly different, as if it’s been waiting to exhale too.

You realize that “ordinary unhappiness” isn’t resignation; it’s recovery.

It’s the hum of truth replacing the static of repression.

And somewhere between the therapy room and the page,

between the fiction and the fact,

you catch that familiar stillness—the one that says:

You don’t need them to hear you.

You only need to have spoken.

That’s the work.

That’s the cure that isn’t a cure.

Mindful, not fearful.

WE&P by: EZorrillaMc.

You must be logged in to post a comment.