A Seamstress at Versailles

Episodes 1–5

Episode 1: The Apprentice in Paris

The rue Saint-Honoré smelled of wet stone and horse dung, but inside Madame Bernard’s workshop the air was sharper: iron needles, beeswax, dyed wool. Catherine bent over her first hem, her eyes blurred from the strain of candlelight. The other girls teased her for her silence, but she had learned that words slipped too easily; stitches, once made, held.

Her master, Madame Bernard, ruled the shop with a cane that never touched flesh but tapped relentlessly against the cutting table whenever hems were crooked. Catherine’s hands, narrow and callused, moved more quickly than the others. She could make linen fold into obedient lines, pull silk taut without bruising it.

Versailles was only a word to her then, spoken with awe and envy by other apprentices. To Catherine, it seemed as far away as Rome or Jerusalem. Her life was bolts of fabric stacked like tombstones, and meals of crusty bread dipped in weak broth. She thought little beyond the next seam—until Madame Bernard summoned her one dawn with an order:

“You’ll carry these gowns to Versailles. Walk carefully. They are worth more than your life.”

Episode 2: Versailles, a Stage of Fabric

The palace rose like a hallucination. Its windows flared with sunlight, dazzling Catherine’s eyes. Inside, the floors gleamed like mirrors; she feared her clumsy shoes would betray the mud of Paris.

She followed a footman down endless corridors, her arms aching from the weight of the gowns. Everywhere she looked, there was movement—ladies in high wigs trailing perfumes of ambergris, men in brocade coats, servants balancing trays of porcelain. She was a shadow among them, invisible, carrying silks wrapped in brown paper.

The workshop within the palace was less divine: crowded, chaotic, fabric everywhere, scissors glinting like daggers. But here, Catherine felt alive. She learned to take a lady’s measure without so much as brushing her sleeve, to pin fabric at a distance respectful yet efficient. Every pleat was rehearsed like a line in a play, every gown a performance in itself.

One afternoon, as she bent to gather discarded ribbons, the air shifted. Silence fell. Catherine looked up.

Marie Antoinette walked past.

She was not the towering figure Catherine had imagined, but light incarnate: pale muslin fluttering, hair powdered like frost, a laugh as soft as spilled sugar. She did not look at Catherine, but the seamstress felt her breath catch. To dress such a woman—was that not like painting on heaven’s canvas?

Episode 3: The Language of Cloth

The other seamstresses whispered constantly—about which duchess favored velvet, which mistress demanded rose-pink silk, which faction at court claimed ownership of lace. Catherine listened, filing it away. She began to understand: garments were not simply worn; they were arguments.

Blue ribbons meant loyalty, fidelity. Green carried rustic charm. White—especially white muslin—was innocence, though sometimes sharpened to irony. Even the angle of a bow could suggest boldness or submission.

She learned to read this grammar with the same hunger she once saved for food. When a marquise demanded a gown of lilac silk, Catherine saw not beauty but strategy: the shade of compromise between rival salons. When a duchess chose black ribbons, Catherine guessed whose funeral—or whose downfall—was being predicted.

Her hands became fluent. Her eyes sharpened. Yet she longed not only to translate but to write. To one day suggest: This cut. This hue. This voice. To let her needle compose.

Episode 4: The Queen’s Whisper

It was the smallest tear—hardly more than a thread snapped in the pale silk sleeve of the Queen’s gown. But in the court of Versailles, the smallest flaw was magnified until it became scandal. Catherine, crouched on the floor among scattered pins, was summoned with a flurry of urgent hands.

“Quick, girl—mend it before anyone notices.”

Her fingers moved without thought. Needle through silk, silk through needle, one careful bite after another. She felt the room hold its breath as she worked, the hush pressing down like a weight. Then—done. The seam was invisible, the silk smooth again. Catherine drew back her hands as though retreating from fire.

Marie Antoinette turned her head. For the first time, her eyes fell directly upon Catherine. They were startlingly blue, framed by lashes dusted with powder. A faint smile lifted her lips.

“You are quick, little one,” the Queen said, her voice both careless and kind. “I will remember.”

It was no more than a passing remark, the sort of phrase a monarch scatters like coins in a street. Yet Catherine felt it strike deep. I will remember.

The words lit a flame inside her. She understood then what she had only half suspected: the Queen’s gowns were not simply clothing. They were armor, theater, diplomacy, illusion. To mend them was not merely to preserve beauty but to protect power.

That night, Catherine could not sleep. She replayed the moment again and again, her heart quickening as though she had been touched by royalty itself. She whispered into the darkness:

“My thread will carry your name.”

And she believed it.

Episode 5: The Birth of the Chemise Dress

The first time she handled the muslin, Catherine thought it too fragile for royalty. It was soft, almost weightless, the fabric of shepherdesses and children’s shifts. Yet the Queen had ordered it, declaring she wanted something “free, unbound, unburdened by whalebone and panniers.”

The workshop buzzed with disbelief. “She cannot mean to wear this,” one marchande muttered. “It is indecent. She will look like a dairymaid.”

But Catherine’s hands trembled with excitement. To drape muslin around the Queen was to sketch a new silhouette, airy as cloud, intimate as breath. She helped pin the first folds, smoothing the fabric against the Queen’s shoulders, seeing how the cloth softened her presence, how it turned majesty into womanhood.

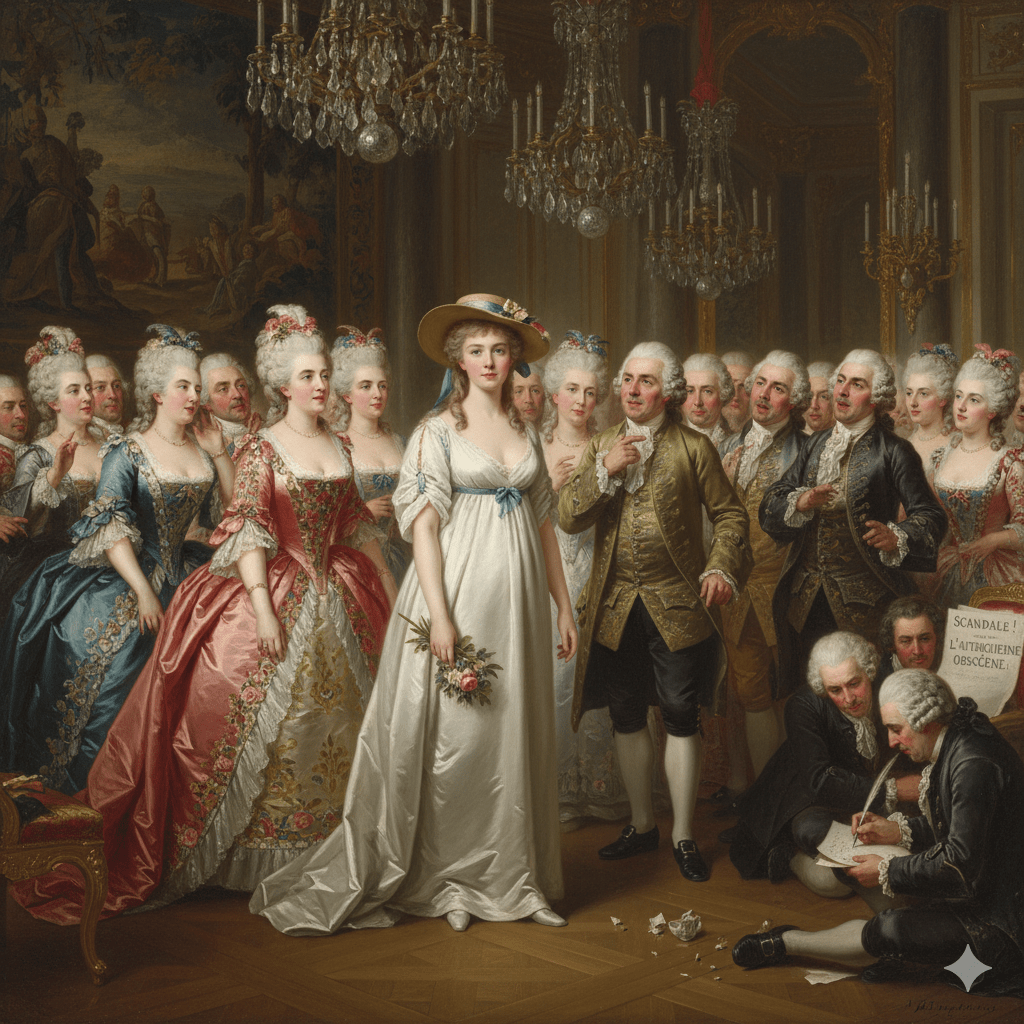

When Marie Antoinette appeared in the chemise gown, the court gasped. Aristocrats hissed—scandalized, outraged. The Queen looked less like a monarch and more like a portrait of Rousseau’s rustic virtue. Pamphleteers sharpened their pens, calling her reckless, even obscene.

Yet outside the court, among common women who glimpsed her portrait, the gown was intoxicating. They saw not a queen disguised as a shepherdess, but a figure daring to cast off constraint.

Catherine stood in the shadows of the fitting room, her heart pounding. She realized she had helped unleash something dangerous, perhaps even revolutionary. This was not merely a gown. It was a manifesto stitched in muslin, a whisper of change that rustled louder than brocade.

For the first time, Catherine felt her needle was no longer just a tool of survival. It was an instrument of history.

WE&P by:EZorrillaMc.

You must be logged in to post a comment.