Part II – The Bridge at Vesterbro (1900s, Pre-War Denmark)

Link to Part I

The winter of 1906 broke with a dampness that sank into walls and bones alike. The canals of Copenhagen ran gray under dripping skies; the snow, when it came, dissolved into slush before it could soften the soot of the city. In salons and taverns alike, conversation turned again and again to the same subject: the death of King Christian IX, Denmark’s Father-in-law of Europe, whose children sat upon the thrones of Britain, Russia, and Greece. His passing closed not only a reign but an era.

At his funeral, the procession was lined with uniforms and sashes of half the continent. Yet behind the glitter of epaulets lay an unease too pressing to be masked by pageantry. Across Europe, labor strikes rose like stubborn weeds through the cracks of empire. In Russia, peasant unrest trembled beneath the boots of soldiers. Even in quiet Denmark, seamstresses whispered of unions, and dockworkers spoke more openly of socialism than of God.

The professor’s salon—once a sanctuary from the city’s noise—now felt more like a listening post for history itself.

The Cedar Box Once More

Professor Anders Thorsen had aged in those sixteen years since that winter in 1890. His beard was streaked with white, his back stooped, yet his gatherings continued, though now with fewer officers and more journalists, clerks, and restless students. His villa on Falkoner Allé seemed smaller, the velvet curtains heavier, as though the old age of dynasties pressed down upon the very walls.

That evening the cedar box returned to its place on the table. Anders no longer laughed when he drew upon the Tarot; he handled the cards as if they were relics.

“Tonight,” he said, voice lower than it once had been, “we let fate choose again.”

He extended the deck toward Ingrid Nielsen, now a woman of middle years, her presence sharper than ever. Her articles had grown in influence; she no longer fought merely for seamstresses’ dignity but for a vision of society in which labor itself was honored. She drew her card and turned it over.

XIII — Death.

The company stirred, some with nervous laughter, others with silence. The card showed a skeletal figure on a pale horse, trampling kings and peasants alike, carrying a black banner.

“An ill omen,” murmured one merchant.

“Not death only,” Anders corrected, eyes narrowing. “Transformation. The end of one order, the beginning of another.” He looked across the fire toward Captain Wilhelm Jørgensen, now graying at the temples, his uniform still neat though the brass no longer gleamed with youth.

Wilhelm’s lips tightened. “The end of order is nothing but chaos. What you call transformation is dissolution.”

Ingrid leaned forward, the fire catching in her eyes. “And yet here we are, Captain, in a Denmark that no longer bends only to the will of kings. The people rise, and they will not be put back to sleep. Even Christian IX’s reign could not stop it. Death has come—to feudal pride, to dynastic privilege. Do you not see?”

Wilhelm did not answer at once. His hand rested on the arm of his chair, fingers tapping as if to the beat of some internal march.

The Strike

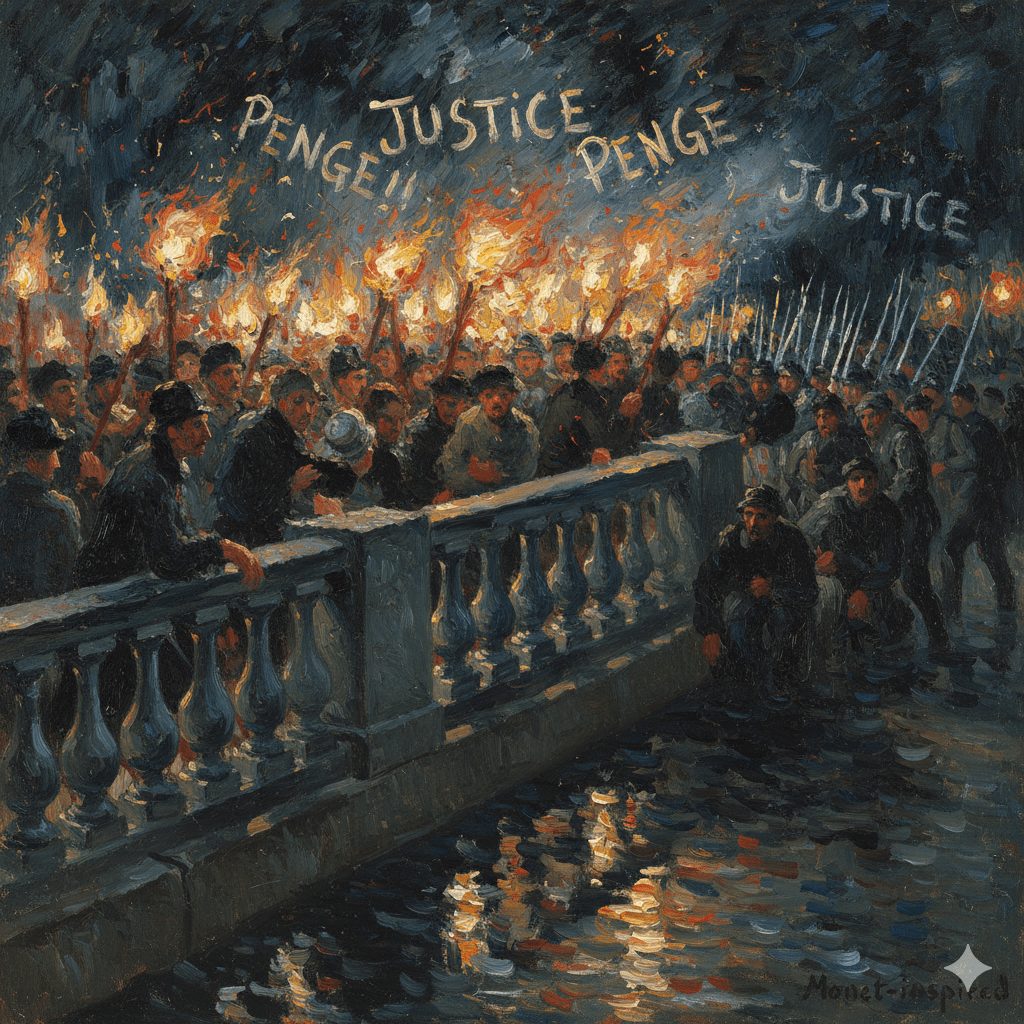

That spring the city trembled with unrest. At Vesterbro, workers of the breweries and rail yards gathered in protest, demanding shorter hours and higher pay. Torches lit the bridge that spanned the narrow river, flames bending in the damp wind. The chants carried across the water, joined by seamstresses and printers, their banners daubed with crude lettering.

Merchants, many of them German, closed their shutters and sent urgent petitions to the council. Soldiers were dispatched but held back, wary of striking against their own countrymen. Rumors swirled of violence.

It was Anders, with his reputation as mediator, who was asked to intervene. He refused to go alone. “This is not a matter for professors,” he told the council. “It is a test for soldiers and journalists alike.” And so he sent for Wilhelm and Ingrid.

The Walk to the Bridge

The three walked together through the wet streets, the air thick with the smell of coal and horses. Posters clung to walls in tatters, some demanding reform, others denouncing socialism as treachery.

Wilhelm marched stiffly, boots striking the stones with soldier’s rhythm. “This is folly,” he muttered. “Workers do not dictate terms to kings or parliaments. Disorder breeds only weakness. It invites the Tysker to our gates again.”

Ingrid pulled her shawl tighter, but her voice was firm. “And what strength do you imagine we have, Captain, if our people live bent and hungry? The death of Christian IX marks more than a king’s passing. It marks the death of obedience. Do you not hear it in their voices?”

Wilhelm stopped, turning to face her. Rain glistened on his mustache, his eyes clouded. “I hear only the death of loyalty.”

Anders, standing between them, spoke softly. “Perhaps both are true. Death clears the field, but what rises after depends on choice. That is why we go to the bridge.”

On the Bridge

The scene at Vesterbro was chaos barely contained. Hundreds pressed against the stone balustrades, torches flaring, voices chanting for penge and justice. Faces were gaunt with hunger, yet fierce with determination. On the other side, merchants clustered in anxious knots, guarded by a thin line of soldiers whose bayonets gleamed in the firelight.

Anders stepped forward first, raising his hands. His words carried little over the noise. Then Wilhelm, by instinct, advanced beside him, his uniform drawing attention. The crowd’s chant faltered.

“I fought for this land!” Wilhelm shouted, his voice hoarse yet strong. “I bled for its soil when Schleswig was torn away. Do you think I do not understand your anger? I do. But if you strike down your neighbors tonight, if you burn what we have, you will give Prussia reason to sneer again that Denmark cannot govern itself. Is that what you want?”

The workers muttered, shifting uneasily.

Then Ingrid moved to his side, her shawl flaring in the wind, her voice carrying with a journalist’s clarity. “You ask what we want? We want to stand as men and women with dignity. We want wages that keep our children alive, hours that let our hands rest, respect enough to meet our neighbors’ eyes without shame. This is not rebellion—it is survival. And if Denmark is to endure, it must endure with us, not against us.”

Silence fell, heavy as the damp air. The torches hissed, rain spitting on their flames. The crowd seemed suspended between violence and retreat.

Wilhelm, chest heaving, looked at Ingrid. “Then let us endure together.”

He turned back to the crowd, lowering his voice, but it carried in the hush. “I am a soldier of the king. But tonight, I stand also as a Dane among Danes. Lay down your fists. Tomorrow we speak again—in council, in parliament, in press. But not here, not with blood.”

Slowly, the tension eased. One by one, the workers lowered their torches. Murmurs replaced shouts. The soldiers shifted, but no command was given.

The bridge held.

Aftermath

When at last the crowd dispersed, the three stood together beneath the dripping eaves of a warehouse. Wilhelm leaned against the wall, his shoulders slack with exhaustion. “It should not be the task of soldiers to make speeches,” he muttered.

“It is the task of men to make choices,” Ingrid replied softly.

Anders looked at them both, the rain streaking his spectacles. “The Death card has spoken. Something has ended tonight—the belief that kings alone hold Denmark upright. What begins…that remains to be seen.”

Wilhelm did not answer. His eyes, dark with weariness, seemed fixed on the torch smoke that drifted upward, lost in the damp sky.

Coda

The following week, negotiations yielded modest gains—shorter hours in the breweries, small increases in wages. It was no revolution, but it was a beginning. The council congratulated itself; the merchants breathed easier. Yet among the workers the word spread: on the Vesterbro bridge, a soldier had stood not against them, but with them.

Ingrid wrote her column with an uncharacteristic restraint, ending with only one line: “What has died is not loyalty, but silence.”

Anders placed the Death card on his mantel, beside The Lovers of years past. The skull-faced rider looked down upon kings and peasants alike, a reminder that the old must die so the new can be born.

Outside, the thaw continued. Snow melted into rivers, rivers into mud. But beneath the mud, seeds waited.

End of Part II

WE&P by: EZorrillaMc.

You must be logged in to post a comment.