Seraphin Durand was measuring the world in quiet ways the morning he met the crow.

He had a habit of drawing grids in his sketchbook before he drew anything else—thin pencil lines, a steady lattice on which he could hang a bridge, a wall, a future vineyard. He’d come to the river to map how the spring flood had chewed the bank, and he had brought his usual kit: cord, stakes, folding rule, a canvas bag with a sandwich wrapped in wax paper, and the little brass compass that clicked shut like a secret.

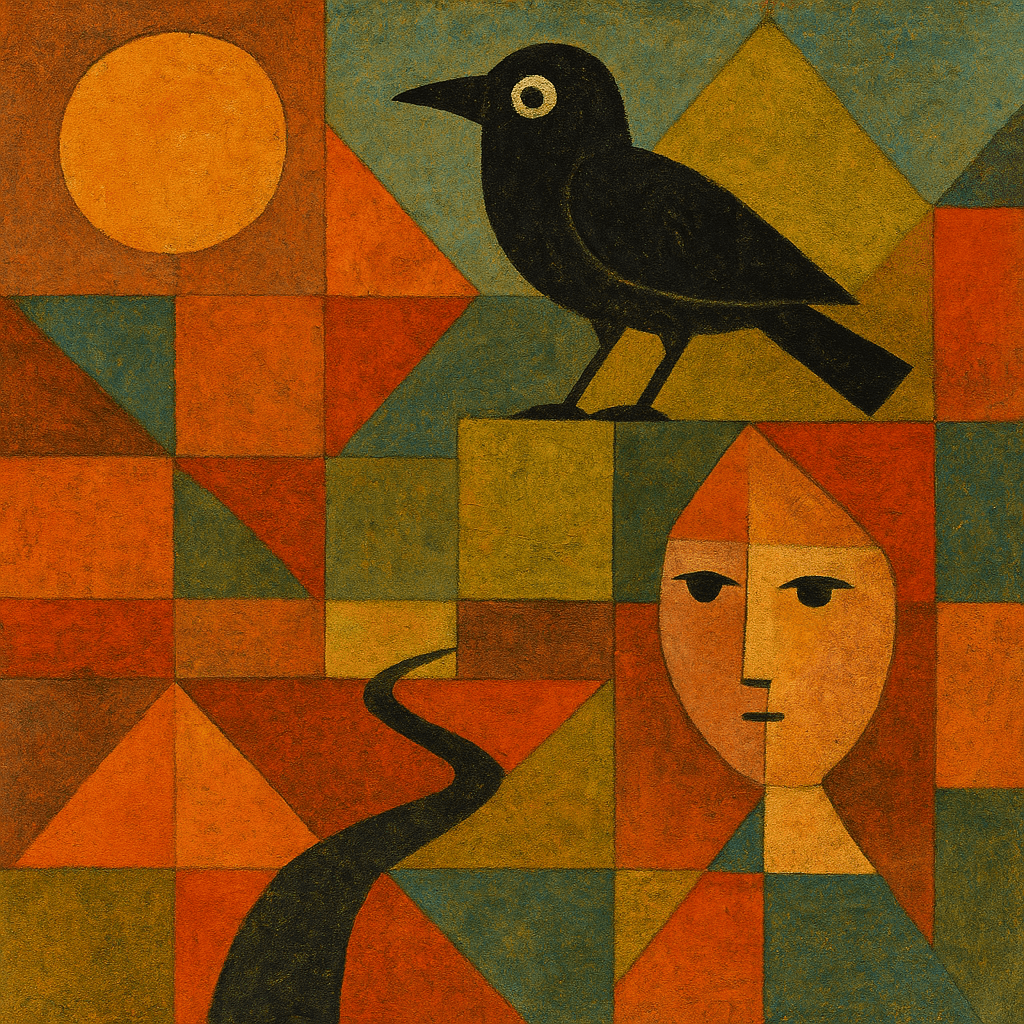

The crow announced itself with the scrape of black on black—a shadow skimming the current, a glossed wing tilted, a bright pin of an eye. It landed on a post two paces from Seraphin and leaned forward, interested in the brass. The bird’s gaze, he thought, felt like a fingertip tapping glass.

Seraphin nodded to it, as one craftsman to another. “Morning.”

The crow hopped down, walked with the surety of a surveyor, and—without ceremony—plucked his compass from the cloth. Seraphin watched it wedge the instrument against the post and worry the hinge with its bill. Clever, he thought—testing the closure, testing him. In a book he’d read on birds of prey from southern latitudes, the author had called certain raptors “big, flashy birds that behave more like crows,” noting how they swaggered up to people, looked them in the eye, and tried to take things from their bags. That line had made him smile at the time. Now the echo of it chimed like a tuning fork: curiosity and nerve were not confined to any one badge of feathers.

He crouched, hands open, setting the terms. “I’ll trade,” he said. The crow cocked its head.

Seraphin drew his sandwich half out of the paper and tore off a crust. He placed it on the post and slid the paper away like a blanket. The bird hopped closer, considering, then dipped to the crust. In that instant Seraphin palmed the compass, clicked it shut, and set it beside the bait, a fair exchange. The crow took the crust, and he reclaimed the instrument, each ritualized theft blessing the other.

He went back to his grid and the river’s edge. The crow followed, landing near the stakes. It watched with concentration as he measured from a fixed datum to a scarp of raw earth, recorded the figure, and tied a tag. It sidled along a branch above his shoulder and made a soft rattling sound, as if turning screws inside its throat.

“You like the work,” Seraphin said. The bird blinked.

He sank the second stake. The crow dropped from its perch, lifted the loose end of his cord in its beak, and tugged. Seraphin felt the line go live in his hand—an invisible partner on the far end. He eased the reel, letting the bird play without snapping the line or his temper. Balance, he reminded himself: the airy part of earth. Measure, then move.

The crow tugged again, then released. It hopped onto Seraphin’s bag and flipped the flap with the side of its bill, nosing through the mouth of the canvas. Seraphin kept an eye on it, recalling another page from that same book: the way island-dwelling birds, especially those called “Johnny rooks” by sailors, had once baffled Darwin with their brazenness—stealing hats, investigating tools, acting like street urchins in feathers. The author had argued that generalists thrive by asking the world a thousand questions, and this crow—though it was no southern raptor—was fluent in that grammar. Reviewers had summed it neatly: the birds in that book shared with corvids an intelligence and curiosity that bent rules and opened latches.

The bag produced, to the crow’s satisfaction, a length of red chalk. The bird lifted it triumphantly and leapt to the post; the chalk left a ping of dust on the wood. The crow pecked once, twice, and the chalk broke into two. It examined the halves, then dropped one and kept the other, as if discovering division.

Seraphin had come to fix the river’s restlessness to numbers—the new line of bank, the angle of slough where the willow had toppled. But another measure emerged: the span between his bent head and the crow’s bright scrutiny; the slow hinge between his fondness for order and the bird’s taste for improvisation. He began to narrate his actions, not because the bird needed them but because he did.

“First line is the base,” he said, setting the cord taut. “Second is the check. You compare. You test your own certainty.”

The crow dropped to the mud, walked the line, and stabbed at a beetle in the seam between roots. It crushed the shell, tossed the morsel into its throat with a flick. Then it hopped onto the stake and gave a brief, grating croak—approval or mockery, Seraphin couldn’t tell.

He took his square and measured an offset from the base line to the scarp. The crow flew to the scarp, landed, and slid a little until it found purchase. It looked like a black thought clinging to a torn page. Seraphin penciled numbers, spoke them under his breath, and paused. The bird raised its wings against a gust; the river breathed in brown and out in silver.

On the third stake, the ground went soft. Seraphin’s boot sank and filled with river-cold. He swore softly—the words came out like stones in a pocket—and the crow lifted, alarmed, to the branch above. He steadied, withdrew his foot with a wet thwup, and set the stake a foot back. The crow settled again, rearranged its feathers, and pretended nothing had happened. It picked up the red chalk half and pressed it, curiously, against the bark, leaving a faint ember smear. A mark—proof of attendance.

“Very well,” Seraphin said. “You can keep that.”

He worked on. The crow’s presence braided with the ordinary sounds—the chuckle of water against a snag, the bell of a distant goat, a truck’s sigh on the far road. Time loosened around the edges. He drew his little plan, annotated with distances, made a note about reinforcing the bank with cribbing and willow cuttings set on the diagonal, so the roots would knit the soil.

When he finally put down the pencil, the crow hopped nearer, the chalk stub clenched in its beak like a flag. It studied his finished drawing, and for an instant—because he was the sort to test his own certainty—Seraphin entertained the impossible: that the bird recognized the diagram as a map of this exact moment. There was, in the book, a suggestion that birds like this learned us as much as we learned them; that attention ran both ways; that a meeting could be a mirror.

He held out his hand. The crow leaned in, and he felt the faint exhalation of its breath. It tipped the chalk into his palm, then plucked it back, an exchange that was not quite either. Seraphin laughed—the sound surprised him. He was not a man quick to mirth, but the bird had smuggled it into his day like contraband.

“Come,” he said. “We’ll walk.”

They set off along the bank: a slow human and a swift idea in feathers. The crow flew ahead, landed, waited; he paced up, took the measure of a gully, a root crown, a natural buttress, and the crow flew on. At the bend the wind opened, and the river widened to show the low island where reeds fretted all summer. The crow arrowed to the island, looped, and returned, bringing with it a length of pale grass. It dropped the strand onto his shoulder as if decorating a statue.

“Thank you,” Seraphin said, gravely. He tucked the grass into the band of his hat.

When he reached the last stake, he raised the reel and let the cord sing through his fingers. The crow chased the line’s shadow like a child, pounced, and rose again. He felt a shift in himself, a loosening of the buckle that cinched him to single solutions. He would still set the cribbing, still weave the willows, still draw the neat plan. But he would leave an aperture for improvisation, a widening to allow the river—and himself—a fraction of play.

He packed his tools. The crow perched on his bag, unwilling to concede possession of the day. He opened the flap, showed his empty hands, and the bird thrust its head in to check. Satisfied—or unwilling to admit defeat—it pulled out a loop of twine and kept it between its toes like a prize. Seraphin let it have the twine. A tax to the guild of cleverness.

Before he left he took one last bearing from the first stake to the drifted log at the waterline. He wrote the angle in his book and closed it gently. The crow peered at him, then at the river, then at him. He touched two fingers to the brim of his hat. The crow responded with a short, buzzing call, as if starting a small engine. Then it lifted, a black hinge opening in the pale afternoon, and flew low along the bank, inspecting the world it would never own but always interrogate.

Walking home, Seraphin realized the meeting had altered his measure of the place. The river’s change had brought him here, but it was the bird’s refusal to leave anything untested—the bag, the hinge, the line, the man—that would stay with him. In that other book, the one about the world’s most inquisitive birds of prey, the writer had argued that intelligence isn’t only the power to act but the urge to ask.

Seraphin, who built things so they would endure, felt a new foundation being poured inside him: not concrete, but curiosity. The crow had set a stake in the day and pulled a line taut between caution and play, between plan and possibility. Tomorrow he would return with willow cuttings and a crew. But today, he carried home a hat decorated with grass and a sketch whose margins bore a faint red smear—a small, bright proof that the world had reached in and left its mark.

WE&P by:EZorrillaMc.

You must be logged in to post a comment.