Part IV: Children of the Shadow (370s–390s AD)

The years turned, and the world grew colder for those who still whispered to the old gods. Julia bore her child—a son, Marcus Aelius—under the hush of secrecy. To the outside world, he was the heir of her Christian husband. In truth, he was the torch passed from Lucius, from Flavia, from generations who had kept the fire alive.

The boy grew among contradictions. In the church, he was sprinkled with holy water, baptized into a faith his parents did not claim. At home, Flavia pressed his hand to the household fire and taught him the names of the Lares. Julia, holding him at her breast, would whisper the prayers of Vesta as lullabies. Aelius, steady as stone, built him wooden toys and taught him how water runs downhill, and how memory—like water—always seeks its own level.

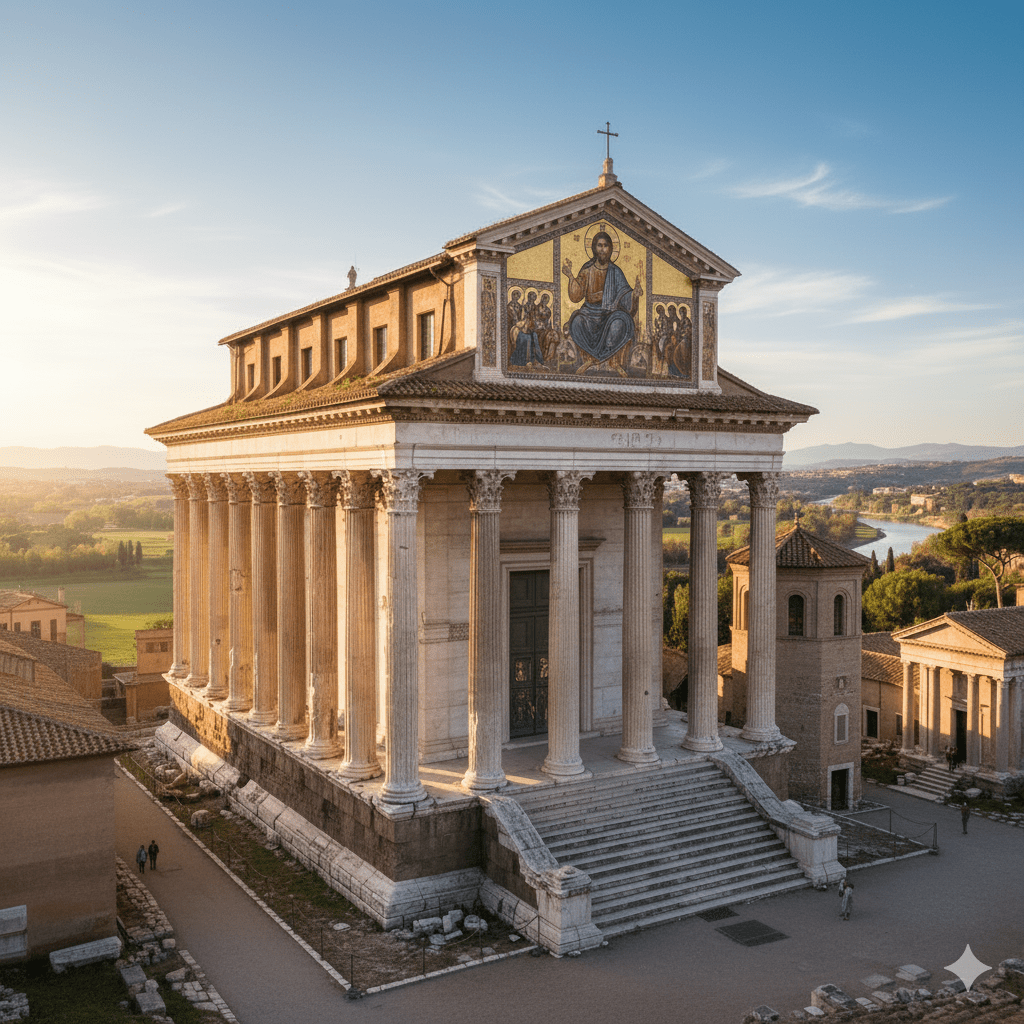

By 385, the city itself had grown hostile. Christian zealots patrolled the streets, overturning shrines, jeering at those who still clung to rituals. The temples were scavenged for marble, their stones re-laid into churches. The Senate, once a chorus of voices raised to many gods, now lowered its eyes beneath the stern gaze of bishops.

Lucius Marcus aged swiftly in this world. He had once been a man of rhetoric, a senator of voice and presence, but each year the space for his words grew smaller. He no longer argued in the Curia, for there was no altar to argue for. Instead, he gathered his grandchildren around him—Marcus Aelius, Sabina’s two daughters, even Marcellus’s illegitimate boy—and told them stories of the old festivals. His voice cracked, but when the children laughed, the sound lit the atrium brighter than any decree from Theodosius.

“Remember,” he told them once, his hand trembling as he pointed to the hearth, “Rome is not stone. Rome is story. So long as you remember, you carry the city in your chest.”

Flavia, ever the realist, salted more meat, kept more coin hidden, and turned her care inward. “Survival is worship too,” she reminded Julia. “A family that endures is its own temple.”

Marcus Aelius grew into boyhood during this twilight. He learned to cross himself in public to avoid suspicion, and then to turn and whisper to the Lares when the door shut behind him. He followed Aelius Cassius to job sites, watching water bend to channels, stone to hands. From Julia, he inherited not only fire but defiance. When a bishop scolded him in the marketplace for laughing too loud, he looked him in the eye and said, “The gods made joy. Do you fear it?” Julia nearly fainted with fear, but secretly, she was proud.

By 390, when Theodosius declared Christianity the only lawful faith of the empire, the family had already learned the art of invisibility. Their rites grew quieter, their prayers shorter. Yet in silence they found endurance. Each loaf of bread baked, each gate mended, each story retold became a kind of ritual, a metaphor made flesh.

The children of that household did not see themselves as rebels. They saw themselves as heirs to habits too old to be erased by decree. They carried blue mosaic chips in their pockets, purple stains on their fingers, the rhythm of bread-breaking in their hands. In every gesture, the old world survived—hidden, fragile, but alive.

Thus the family endured: a senator turned storyteller, a matron turned guardian of memory, a daughter turned mother of fire, and a son-in-law who built drains against the flood. Against the empire’s decrees, they offered not revolt, but persistence. Against forgetting, they offered memory. Against erasure, they offered the stubborn flame of habit.

The world around them crumbled, shifted, remade itself in new images. But within the Marcus and Cassius households, in the years after 370, the fire never went out.

Part V: The Waning Empire (Early 5th Century AD)

The dawn of the fifth century brought winds colder than any edict. The Western Empire itself groaned under the weight of its own neglect. Barbarians pressed at the borders, tax collectors squeezed coin from stone, and Rome—eternal in name—was beginning to look mortal.

Within the Marcus and Cassius households, the fire still burned, but the city outside seemed less like a marble monument and more like a cracked amphora, leaking strength with every season.

Marcus Aelius, son of Julia and Aelius, was now a man. Tall, lean, and sharp-eyed, he bore both his father’s patience and his mother’s restless defiance. He had learned to bow his head in the basilica when the bishop passed, but his truest reverence was reserved for the hearth. When he married, it was under the church’s roof—but in secret, Julia placed her hand on his and whispered the words of Vesta.

By now, Lucius Marcus had passed, carried to his pyre with more secrecy than he deserved. The law demanded burial in Christian manner, but Julia and Flavia, with Sabina and Quintus at their side, gave him fire as the gods had always commanded. The flames rose on a moonless night, shielded by trees outside the city wall. Marcus Aelius, watching, understood: even in an empire where the old rites were outlawed, love could not be legislated.

The city he inherited was poorer, meaner. Statues once honored were toppled, their faces hammered smooth. Temples were stripped bare for lime and brick. The Senate itself, once Rome’s voice, had become an echo chamber of bishops and bureaucrats. To be a pagan now was not merely unfashionable—it was dangerous.

Yet the household endured. Flavia, silver-haired and iron-hearted, became the matriarch of memory. Her voice carried the weight of three generations of hidden ritual. “Every loaf of bread is an offering,” she told her grandchildren. “Every fire you light is Vesta’s, whether you name her or not.”

Marcus Aelius carried these lessons into a world that was fraying at the edges. He took work along the Tiber, shoring up walls against floods that seemed to come with every winter. He built drains, repaired aqueducts, argued with overseers. “Stone does not care about decrees,” he told his apprentices. “It holds if you set it right. It fails if you cheat. Remember that.” In his words, the gods still spoke.

By 410, the unthinkable came to pass: Alaric’s Goths stood at the gates of Rome. Panic surged like a flood. Some blamed the Christians for abandoning the old gods; others blamed the pagans who still clung to them. In the Marcus atrium, the fire was tended carefully, though every sound from the street threatened to smother it.

On the night the city fell, Julia—now gray, her fire undimmed—took her grandson’s hand and placed the mosaic chip she had carried since girlhood into his palm. “Keep this,” she said, voice firm even as shouts and flames echoed in the distance. “A fragment of sky. When the walls fall, look up. The gods are not in stone. They are in your memory, your habit, your fire.”

The boy, scarcely twelve, clutched the chip as the city shook around them. In that moment, the line held. Against the fall of Rome, against the roar of invaders, against the edicts of emperors—the fire passed on.

Part VI: Ashes and Roots (Mid 5th Century AD)

After the sack of Rome, nothing seemed permanent. The marble city, once eternal, felt brittle. Aristocrats fled to villas, bishops filled the void, and families like the Marcuses and Cassii learned to live in the cracks of a broken world.

Marcus Aelius, now middle-aged, bore the weight of survival. He had kept the family alive through famine, through raids, through the grinding demands of tax collectors. He raised his children to walk softly in the basilicas, to nod when bishops spoke, but also to know the names of the Lares whispered at night. His wife, Livia, lit the household fire each dawn, her hands steady though her neighbors thought her motions merely habit, not worship.

Julia, old now but unyielding, became legend within her household. To her grandchildren she was the embodiment of both memory and defiance. She no longer needed to say much—her presence by the hearth, her silence when prayers to saints were spoken, reminded them that the old Rome still breathed in secret.

By mid-century, the world grew more fragile still. Vandals cut through Africa, and with them went the grain that once fed Rome. The Tiber valley starved, and Marcus Aelius bartered stonework for sacks of barley. “Every wall is temporary,” he told his son, Lucian. “But every story you repeat lasts longer than stone.”

Lucian grew into the fifth generation to guard the fire. He was restless, less cautious than his father, more like Julia in her youth. He carried the mosaic chip in a leather pouch, showing it to friends he trusted. “This is sky,” he told them. “Sky you can hold.” To him, the old gods were not relics but metaphors for endurance—habits wrapped in myth. He believed survival was not just hiding but adapting, shaping old truths into new words.

When Attila’s Huns thundered through Italy in the 450s, panic swept the land. The bishop of Rome went out to meet the conqueror, and somehow the city was spared. To the world, it was a triumph of Christian authority. To the Marcus household, it was proof that survival itself was divine. Around the hearth, Lucian told his siblings: “Whether it is Christ or Jupiter who spares us, what matters is that the story continues. We carry both gods and memory.”

The family’s villa shrank, its marble stripped, its library thinned. Yet the hearth remained. When Julia finally passed, her body was buried with Christian rites, but in her hands Lucian slipped the mosaic chip. “Carry the sky,” he whispered. “Carry us.”

Part VII: Twilight of the West (Late 5th Century AD)

By 476, when Romulus Augustulus was deposed and the Western Empire itself fell, the Marcus-Cassius line endured. They were no longer senators or builders of aqueducts; they were farmers, traders, keepers of stories. The name Marcus carried little weight in the courts of new barbarian kings, but at the hearth, it was still spoken with reverence.

Lucian’s children grew up in a world where Rome was not an empire but a memory. Yet the fire was still lit each morning. The prayers—shorter now, half in Latin, half in rustic dialect—were still whispered. The mosaic chip still passed from hand to hand, a relic of sky older than kingdoms.

“Empires fall,” Lucian told them, his hair silver in the firelight. “But fire rises. Stones crumble, but memory remains. We are Romans not because we live in Rome, but because we remember Rome. And memory is the truest empire.”

The children listened, as Julia had once listened to her father Lucius, and as Lucius had once listened to his ancestors. The circle closed, the story renewed. Against the fall of the Western Empire, against the ashes of marble and the silence of temples, the fire passed on.

Part VIII: After the Fall (6th Century AD)

When the last emperor in the West was gone, Rome did not vanish—it shifted. The Ostrogoths ruled Italy for a generation, then the Byzantines came with their soldiers and their crosses, and finally the Lombards swept down, carving the peninsula into fractured kingdoms. Yet the Marcus-Cassius family, reduced in status but not in memory, endured.

Lucian’s children became farmers in the hills outside Rome. They no longer spoke Latin as senators once did; their tongue was rustic, clipped, flavored by the speech of neighbors from distant lands. Yet each dawn, before work in the fields, the fire was lit. The words had changed, softened, half-prayer, half-proverb, but the meaning remained: Vesta’s flame, even unnamed, was still honored.

By 540, when Justinian’s general Belisarius retook Rome for the empire of the East, the city was already a shadow of itself. Its population had dwindled, its aqueducts broken, its grand forums turned to pasture. In one ruined district, the descendants of Julia Marcus still kept a modest home. The mosaic chip, handed down for generations, was now worn smooth from countless fingers. Children no longer knew the names of Jupiter or Minerva, but they were told, “This is sky. Hold it, and remember.”

It was memory, not marble, that survived.

When plague struck, when famine gnawed, when Lombard warbands cut through the countryside, the family endured by humility. They offered bread to both soldier and monk. They crossed themselves in the church, but at night told stories of ancestors who once poured wine for unseen gods. “The gods are habits,” Lucius had once said. And habit proved stronger than empire.

By the end of the sixth century, the line had settled into obscurity. They were no longer senators, no longer builders of aqueducts, but their household remained a temple of sorts: a place where memory was guarded, where children learned that identity does not vanish with the fall of walls.

Epilogue: Embers

The story of the Marcus-Cassius line is not one of conquest or triumph. It is the story of fire carried in cupped hands across storms. Rome fell. Kingdoms rose and crumbled. Faiths shifted. Languages bent. Yet within a modest house, a fire was still lit each morning, a story was still told at night.

Julia’s mosaic chip, that fragment of sky, was passed from hand to hand until its edges blurred. It became less a relic of a temple and more a symbol of endurance. To the children who held it, it whispered that the past was not erased—it was transformed.

And so the last pagan generation became the first generation of memory-keepers. Their defiance was not loud but lasting. Against decrees, against ruins, against the weight of forgetting, they chose to remember.

For what is Rome if not a fire kept alive through the long night? What is any people, any family, if not the guardians of their own embers?

The empire fell. The family endured. And in their endurance, Rome—eternal not in stone but in story—lived on.

The End

WE&P by: EZorrillaMc.

One-Page Synopsis

The Last Fires of Vesta

A Historical Novella in Multiple Parts

Title: The Last Fires of Vesta

Genre: Historical Fiction / Literary Saga

Length: Novella (~5000+ words, multi-part)

Overview

The Last Fires of Vesta is a multi-generational saga following a Roman family through the decline of pagan traditions and the rise of Christianity in the late Roman Empire. Inspired by historical scholarship (The Final Pagan Generation by Edward J. Watts, and A.D. 381 by Charles Freeman), the novella humanizes this great cultural transition through the intimate story of love, memory, and resilience.

Plot Summary

- Part I: The Parents’ Golden Years (370s AD)

Lucius Marcus, a senator, and his wife Flavia maintain their household rites to the old gods even as the empire shifts toward Christianity. Across the city, engineer Priscus Cassius and his wife Domitia live with equal devotion in private. Their children—Julia Marcus and Aelius Cassius—grow up amid these competing worlds, carrying fragments of tradition. - Part II: Coming of Age (380s AD)

Julia, fiery and defiant, and Aelius, steady as stone, mature under Christian dominance. Together with their friends Marcellus, Quintus, and Sabina, they form a tight-knit circle. As laws outlaw sacrifice and close temples, the group learns to disguise their rituals, turning memory itself into resistance. Julia and Aelius’s affection deepens, set against the backdrop of imperial decrees. - Part III: The Secret Wedding (382 AD)

Forced to marry under the Christian rite, Julia nonetheless claims her heritage. In a hidden ceremony at home, she and Aelius wed by the hearth in the name of Vesta and the Lares. This dual wedding symbolizes the family’s survival strategy: outward conformity, inward fidelity to tradition. Julia soon conceives, carrying the fire into the next generation. - Part IV: Children of the Shadow (370s–390s AD)

Their son, Marcus Aelius, is raised in secrecy—baptized in church but dedicated at home to the household gods. Lucius grows old, teaching the children that Rome is not stone but story. Flavia ensures the household survives through prudence, while Julia whispers the old prayers as lullabies. - Part V: The Waning Empire (Early 5th Century AD)

The family endures famine, raids, and the sack of Rome in 410. Julia entrusts her grandson with a mosaic chip she had carried since childhood, calling it a fragment of sky. “When the walls fall, look up,” she tells him, affirming memory as survival. - Part VI: Ashes and Roots (Mid 5th Century AD)

Reduced to farming and trade, the family preserves its identity through habit rather than grandeur. The gods’ names fade, but their essence lingers in proverbs, bread, and firelight. Julia’s descendants keep the flame quietly alive. - Part VII: Twilight of the West (Late 5th Century AD)

As the Western Empire collapses in 476, the Marcus-Cassius line survives in obscurity. They no longer shape empires, but they keep the fire and the story alive for their children. - Part VIII: After the Fall (6th Century AD)

Through Ostrogothic, Byzantine, and Lombard rule, the family endures as memory-keepers. The mosaic chip, worn smooth from generations of hands, becomes a relic of survival. By now the old gods are forgotten, yet their essence lives on in ritual, habit, and love. - Epilogue: Embers

The saga concludes not with conquest, but with continuity. The family’s quiet defiance proves that memory, not marble, is eternal. Rome falls, but the fire of Vesta survives in the hearts of those who remember.

Themes

- Memory vs. Forgetting: The novella emphasizes how traditions survive not through monuments, but through habits and stories.

- Love and Defiance: Julia and Aelius embody resilience, carrying their devotion into secrecy.

- Generational Continuity: Each generation finds a new way to preserve meaning despite political upheaval.

- Metaphor of Fire: The hearth flame symbolizes continuity, adaptation, and survival.

Intended Audience

For readers of historical fiction, classical studies, and anyone fascinated by cultural transitions. Especially suited to college-educated readers who appreciate historical depth, metaphorical resonance, and character-driven narrative.

The Last Fires of Vesta is a story of how civilizations truly endure—not in marble and decree, but in memory passed from hand to hand, like a fragment of sky kept safe against forgetting.

You must be logged in to post a comment.