Master Your Emotions: A Guide to Emotional Success Through Adlerian Psychology

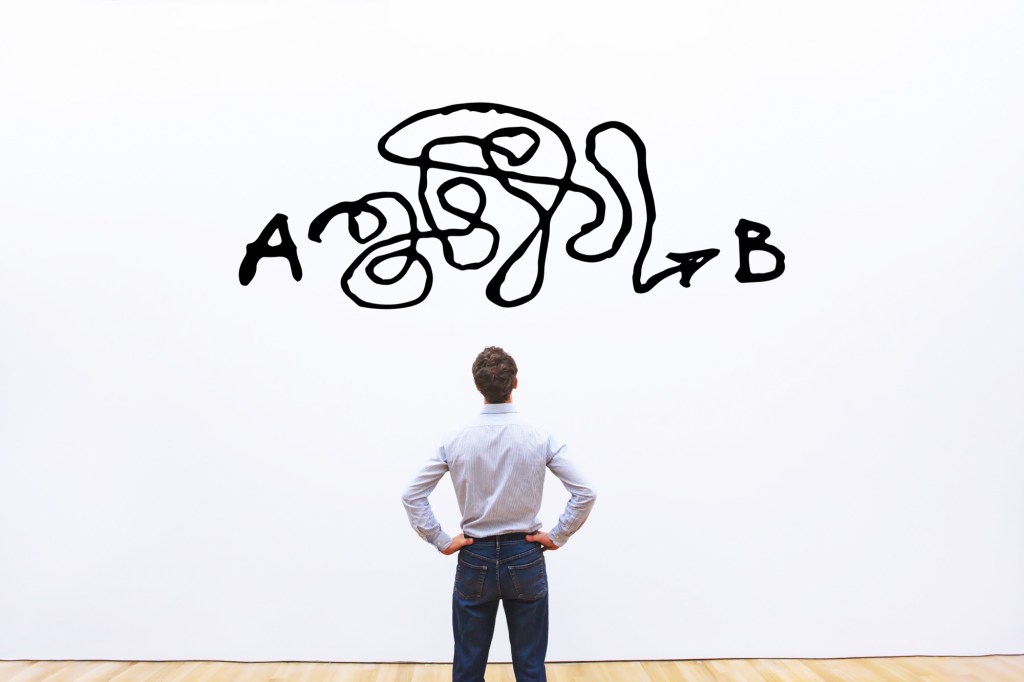

Achieve emotional well-being and navigate interpersonal conflicts with greater ease by embracing the principles of Adlerian psychology. Developed by Alfred Adler, this school of thought offers a hopeful and practical framework for understanding ourselves and our relationships, positing that we all have the capacity for personal growth and emotional success. This guide will walk you through the core tenets of Adlerian psychology and provide concrete examples for resolving emotional disputes.

The Cornerstones of Emotional Success: An Adlerian Perspective

Adlerian psychology is built on several key principles that, when understood and applied, can lead to profound emotional growth.

1. The Striving for Significance and Belonging: At our core, humans have a fundamental need to feel a sense of belonging and to know that we matter. Emotional distress often arises when we feel disconnected, insignificant, or inferior. True emotional success, therefore, is not about being perfect, but about finding our place within a community and contributing in a meaningful way.

2. Overcoming Feelings of Inferiority: Adler believed that feelings of inferiority are a natural part of the human experience, starting in childhood. These feelings can be a powerful motivator for growth and achievement. However, when these feelings become overwhelming, they can lead to an “inferiority complex” and emotionally unhealthy behaviors. The goal is to acknowledge these feelings and use them as a springboard for positive change, rather than letting them define us.

3. The Power of Social Interest (Gemeinschaftsgefühl): This German term, which translates to “community feeling” or “social interest,” is the bedrock of Adlerian psychology. It refers to our innate ability to empathize with others and to act in a way that benefits the greater good. A well-developed sense of social interest is considered the hallmark of a psychologically healthy individual. The more we cultivate our social interest, the more emotionally fulfilled we will be.

4. Goal-Oriented Behavior: Adler saw all human behavior as purposeful and goal-oriented, even if we are not consciously aware of our goals. Our actions are driven by our unique “lifestyle,” a pattern of behavior that we develop in childhood to navigate the world and find our place in it. Understanding the underlying goals of our own and others’ behavior is crucial for emotional intelligence and conflict resolution.

5. The Unity of the Individual: Adlerian psychology takes a holistic view of the person. Our thoughts, feelings, and actions are all interconnected and work together to achieve our goals. To understand a specific behavior, we must look at the individual as a whole and the context in which they are operating.

Navigating Emotional Interpersonal Conflict: An Adlerian Toolkit

Adlerian psychology views interpersonal conflict not as a battle to be won, but as a breakdown in cooperation. The following strategies, rooted in Adlerian principles, can help you resolve disputes in a way that fosters connection and mutual respect.

1. Practice Encouragement, Not Praise:

Praise often focuses on achievement and can foster a sense of competition. Encouragement, on the other hand, focuses on effort and intrinsic worth. In a conflict, encouragement can validate the other person’s feelings and build their self-esteem, making them more open to a resolution.

- Example: Instead of saying, “You finally did the dishes, that’s great,” which can sound condescending, try, “I really appreciate your effort in helping to keep our home clean. It makes a big difference to me.”

2. Seek to Understand the Other’s Perspective:

Empathy is a cornerstone of social interest. Before reacting, take a moment to consider the situation from the other person’s point of view. What might be their underlying feelings of inferiority or their mistaken goals that are driving their behavior?

- Example: If a coworker is constantly critical of your work, instead of becoming defensive, consider that their criticism might stem from their own feelings of inadequacy and a mistaken goal of proving their superiority.

3. Identify the Goal of the Behavior:

Ask yourself, “What is this person trying to achieve with their behavior?” Adler identified four mistaken goals of misbehavior, which can also be applied to adult conflicts: attention, power, revenge, or displaying inadequacy.

- Example: During an argument, if your partner becomes silent and withdrawn, they might be pursuing a mistaken goal of power by forcing you to be the one to re-engage. Recognizing this can help you respond more effectively, perhaps by giving them space and then addressing the issue calmly later.

4. Focus on Cooperation and Mutual Respect:

Frame the conflict as a shared problem that you can work together to solve. This shifts the dynamic from adversaries to collaborators. Emphasize that you are on the same team and that you both want a positive outcome.

- Example: In a disagreement about finances, instead of blaming each other (“You spend too much!”), try a cooperative approach: “We seem to have different ideas about our budget. How can we work together to create a financial plan that we both feel good about?”

5. “Act As If”:

This technique involves behaving “as if” you already possess the qualities you wish to embody in the situation. If you want to be more patient, act as if you are a patient person. This can help to break old patterns of behavior and create new, more positive interactions.

- Example: If you tend to get angry during disagreements with your teenager, before the next conversation, decide to “act as if” you are a calm and understanding parent. This conscious choice can change the entire tone of the interaction.

6. Take Responsibility for Your Contribution:

Acknowledge your role in the conflict. This is not about blaming yourself, but about recognizing that every interaction is a two-way street. Taking responsibility can de-escalate the situation and encourage the other person to do the same.

- Example: You could say, “I realize that I was not listening to you earlier, and I’m sorry. I want to understand what you are trying to say.”

By integrating these Adlerian principles and techniques into your daily life, you can cultivate greater emotional intelligence, build stronger and more fulfilling relationships, and navigate the inevitable challenges of interpersonal conflict with grace and wisdom. Emotional success is not about avoiding problems, but about having the tools to face them constructively and with a deep sense of connection to others.

The Way of the Heart: A Guide to Emotional Success Through Rumi’s Ideology

The 13th-century Persian poet and Sufi mystic Jalaluddin Rumi was more than a poet; he was a guide to the inner life. His work offers a profound and timeless path to emotional success, one that is built not on suppressing feelings but on transmuting them through the transformative power of Love. This guide will walk you through the core of Rumi’s ideology and provide examples for navigating the turbulent waters of interpersonal conflict.

The Foundations of Emotional Success: Rumi’s Vision

At the heart of Rumi’s teachings are several key principles that reframe our understanding of emotional well-being.

1. Your Heart is a “Guest House”:

Rumi’s famous poem, “The Guest House,” is a cornerstone of his emotional philosophy. He urges us to treat every emotion—joy, grief, anger, jealousy—as an honored visitor. Emotional success is not the absence of difficult feelings, but the ability to welcome them without judgment, listen to their message, and allow them to pass through without becoming attached to them.

“Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they’re a crowd of sorrows,

who violently sweep your house

empty of its furniture,

still, treat each guest honorably.

He may be clearing you out

for some new delight.”

2. The Primacy of Universal Love (Ishq):

For Rumi, Love is the fundamental reality of the universe. It is the force that connects everything and everyone. Emotional suffering arises from the illusion of separation—from others, from our true selves, and from the Divine. The path to emotional success is the path of return to this universal love, which dissolves fear, anger, and blame.

3. The Purpose of Pain and Heartbreak:

Rumi does not advocate for avoiding pain. Instead, he sees it as a sacred tool for spiritual and emotional growth. Hardship cracks open the shell of our ego, allowing the light of understanding and compassion to enter.

“The wound is the place where the Light enters you.”

An emotionally successful person, in Rumi’s view, understands that conflict and sorrow are not punishments, but opportunities to deepen their capacity for love and empathy.

4. The Ego (Nafs) is the Source of Conflict:

Rumi identifies the ego, or the false self, as the root of our emotional turmoil. The ego thrives on being right, on judgment, on grievance, and on feeling superior or victimized. True emotional freedom comes from recognizing the ego’s tricks and choosing to act from the heart, or the true Self, instead.

Navigating Emotional Interpersonal Conflict: A Rumi-Inspired Toolkit

When faced with conflict, Rumi’s wisdom asks us to shift our goal from winning the argument to deepening the connection.

1. Meet in the “Field Beyond Right and Wrong”

This is perhaps Rumi’s most famous piece of guidance for conflict. The concepts of “right” and “wrong” are the territory of the ego. To resolve a conflict, you must be willing to step out of the mental battlefield of blame and judgment and into a space of pure connection.

“Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

there is a field. I’ll meet you there.”

- Example: You are in a heated argument with your partner about being late. The “right and wrong” battlefield is about whose time is more valuable and who is being disrespectful. To move to the “field,” you would stop the debate and ask a different question: “It feels like we are hurting each other right now. Can we pause this and talk about the feeling of being disconnected that’s really underneath this?”

2. Listen with the Ear of the Heart

Conflict is often driven by people talking at each other, defending their own positions. Rumi urges us to listen for what is not being said—the pain, fear, or unmet need behind the angry words. This is listening with the heart.

- Example: A coworker snaps at you over a small mistake on a project. Your ego wants to snap back and point out their mistakes. Instead, you listen with the heart. You might recognize the panic and stress in their voice and respond with, “It sounds like you’re under a lot of pressure with this deadline. I’m sorry I added to it. How can I help make it right?”

3. Examine Your Own Ego

Before you can resolve an external conflict, you must look at your internal one. When you feel triggered, Rumi’s wisdom asks you to pause and question your reaction. Is your anger truly about the other person’s action, or is it because your ego feels slighted, disrespected, or embarrassed?

- Example: Your friend cancels plans at the last minute. You feel a surge of anger. Before sending an accusatory text, you pause and ask: “What’s really hurting here?” You might realize the anger is a shield for the deeper pain of feeling unimportant. This self-awareness allows you to respond from a place of vulnerability rather than aggression, perhaps by saying, “I was really looking forward to seeing you and I feel disappointed.”

4. See the Conflict as a “Polishing” of Your Mirror

Rumi often used the metaphor of the heart as a mirror that must be polished to reflect the divine light. Interpersonal conflicts are the rags and polish. They are abrasive and uncomfortable, but they scrub away the rust of our ego, pride, and judgment, leaving our hearts clearer and more reflective of love.

- Example: You have a recurring conflict with a family member who holds vastly different political views. Instead of seeing them as an adversary, you can reframe the situation as a spiritual practice. This person is your “polisher.” Each interaction is a chance to practice patience, to see the shared humanity beneath the differing beliefs, and to polish away your own reactive and judgmental tendencies.

By embracing these principles, you begin to see every emotional challenge and interpersonal conflict not as a problem to be eliminated, but as a sacred invitation—an opportunity to dissolve the ego, open the heart, and connect more deeply with the universal love that Rumi recognized as our true home.

Where Id Was, There Ego Shall Be: A Freudian Guide to Emotional Success

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, offered a revolutionary and challenging map of the human mind. A Freudian path to “emotional success” is not about finding constant happiness, but about achieving a deep and sometimes unsettling self-awareness. It is the process of gaining mastery over the primal, unconscious forces that drive our behavior. Success, in this view, is the triumph of reason and reality over raw instinct and internalized guilt.

The Freudian Map of Your Inner World

To achieve emotional success, you must first understand the key players in your internal psychic drama.

1. The Id, Ego, and Superego:

Freud posited that our personality is composed of three competing elements:

- The Id: The primal, instinctual part of your mind that operates on the pleasure principle. It seeks immediate gratification for all desires, wants, and needs. It is the impulsive child within, shouting “I want it now!”

- The Superego: The moral conscience, operating on the principle of morality. It is the internalized voice of parents, society, and authority, telling you what you “should” and “should not” do. It wields guilt and shame as its primary tools.

- The Ego: The rational mediator, operating on the reality principle. The Ego’s job is to satisfy the Id’s desires in a way that is realistic and socially acceptable, while also appeasing the Superego.

Emotional success is the development of a strong Ego—an executive self that can skillfully manage the impulsive demands of the Id and the rigid prohibitions of the Superego without being overwhelmed by anxiety.

2. The Unconscious Mind:

Freud’s most enduring concept is that the most significant parts of our mind are hidden from us. Like an iceberg, only a small tip (the conscious mind) is visible. The vast, submerged portion (the unconscious) contains our repressed memories, hidden desires, deep-seated fears, and unresolved childhood conflicts. These hidden forces powerfully influence our emotions, reactions, and relationships. The core Freudian goal is to “make the unconscious conscious.”

3. Defense Mechanisms:

When the Id and Superego clash, the Ego experiences anxiety. To protect itself, the Ego employs various defense mechanisms—unconscious strategies that distort reality to reduce psychological distress. While sometimes useful, over-reliance on them prevents emotional growth. Key examples include:

- Projection: Attributing your own unacceptable thoughts or feelings to someone else.

- Displacement: Redirecting an emotional response from its original target to a less threatening one.

- Denial: Refusing to acknowledge a painful reality.

- Sublimation: Channeling unacceptable impulses into socially constructive activities (considered a mature defense).

A Psychoanalytic Toolkit for Emotional Interpersonal Conflict

A Freudian approach views interpersonal conflict as an external manifestation of an internal war. The person you are fighting with is often a stand-in for a deeper, unresolved issue.

1. Identify the Defense Mechanisms at Play

The first step in resolving conflict is to become a detective of the psyche—both your own and the other person’s. Ask yourself: what defense mechanisms are being used here?

- Example: You have a bad day at work where your boss belittles you. You come home and start a fight with your partner over something trivial, like how the dishwasher was loaded. This is a classic case of Displacement. You are transferring the anger you couldn’t express towards your boss onto a safer target.

- How to Deal: Acknowledge the mechanism. Stop and say, “I’m realizing my anger isn’t really about the dishwasher. I had a terrible day at work and I’m taking it out on you. I’m sorry.” This act of making the unconscious process conscious immediately defuses the irrational conflict.

2. Look for Transference

Transference is a core Freudian concept where you unconsciously redirect feelings and attitudes from a person in your past (often a parent) onto a person in your present. It is a massive source of conflict.

- Example: Your boss gives you constructive feedback, but you react with intense feelings of shame and anger because their tone reminds you of a hyper-critical father. You are not just reacting to your boss; you are reacting to your father through your boss. This is transference.

- How to Deal: Practice introspection. Ask yourself: “Does this person’s behavior remind me of anyone else? Is the intensity of my emotional reaction proportional to the current situation?” By recognizing the pattern, you can separate the past from the present and respond to what is actually happening, not what your history is telling you is happening.

3. Strengthen Your Ego (The Mediator)

In a heated argument, your Id wants to scream and lash out. Your Superego might tell you to shut down and accept all blame to be a “good” person. A strong Ego finds the path of reality.

- Example: A friend accuses you of being selfish.

- Id response: “Well, you’re a needy jerk!”

- Superego response: “You’re right, I’m a terrible friend, I’m so sorry.” (Even if the accusation is unfair).

- Ego response: “I’m hurt by what you’re saying. I don’t see myself that way, but I want to understand why you feel that way. Can you give me a specific example so we can talk through it?”

- How to Deal: In moments of conflict, pause. Take a breath. Actively choose to respond from your rational mind rather than your impulsive drives or your guilt complex.

4. Practice Sublimation

Freud believed that we all have a reservoir of aggressive energy (part of the Id). If this energy isn’t channeled, it can erupt in destructive ways, such as picking fights. Sublimation is the mature defense of channeling that raw energy into something productive.

- Example: You feel constantly irritable and find yourself on the verge of arguments with loved ones. Instead of letting that aggression poison your relationships, you can sublimate it. Take up a competitive sport like boxing or tennis, throw yourself into a demanding project at work, or engage in a vigorous creative pursuit.

- How to Deal: Recognize when you are feeling aggressive or agitated and find a constructive outlet. This drains the psychic pressure and makes you less likely to use a person as a release valve.

By applying these Freudian tools, you can move from being a passenger in your emotional life, driven by hidden forces, to becoming the driver. It is a challenging journey of self-exploration, but it holds the promise of true emotional mastery: a life guided not by unconscious compulsion, but by conscious choice.

Living in the Now: A Guide to Emotional Success Through Eckhart Tolle’s Teachings

Eckhart Tolle’s philosophy offers a radical path to emotional success, which he defines not as a life of constant highs, but as a deep and abiding inner peace that is unshaken by external events. This success is achieved by understanding and transcending the mind’s dysfunctional patterns. This guide will walk you through Tolle’s core concepts and provide practical examples for navigating emotional interpersonal conflict.

The Foundations of Emotional Success: Tolle’s Core Concepts

According to Tolle, all emotional suffering stems from a single source: our identification with the thinking mind and our loss of the present moment.

1. The Power of Now:

This is the central pillar of Tolle’s teaching. He posits that there is no past or future—they exist only as thoughts in your head. The only reality is the present moment. When we dwell on past grievances or future anxieties, we create psychological suffering. Emotional success is the ability to anchor your awareness in the Now, where problems, in the conventional sense, do not exist.

2. The Egoic Mind:

The ego is a false, mind-made self. It is the “story of me”—a collection of past memories, future projections, and identifications (my job, my beliefs, my possessions). The ego is inherently dysfunctional. It thrives on conflict, drama, comparison, and grievance. It constantly seeks to be “right” to fortify its sense of self. Emotional turmoil is the direct result of being possessed by the ego.

3. The Pain-Body:

Tolle describes the pain-body as a semi-autonomous energy field within us, composed of accumulated old emotional pain. It’s the residue of every painful experience you’ve ever had. This “pain-body” lies dormant most of the time but gets activated by specific triggers. When it awakens, it takes you over, and you become your pain. It seeks to feed on more pain, which is why it is a primary driver of intense interpersonal conflict and self-sabotage.

4. Presence: Disidentifying from the Mind:

The solution to the ego and the pain-body is Presence. This is a state of intense, non-judgmental awareness. You achieve it by becoming the “watcher” of your thoughts and emotions. When you observe your mind, you realize that you are not the thoughts, but the silent awareness behind the thoughts. This creates a separation, a space where you are free from the mind’s compulsive control.

A Practical Toolkit for Emotional Interpersonal Conflict

Tolle’s approach to conflict is to transform it from the inside out. The goal is not to “win” the argument but to use it as a powerful spiritual practice to awaken into Presence.

1. Practice Non-Reaction

When faced with an attack, criticism, or negativity, the ego’s instinct is to react immediately—to defend, deny, or counter-attack. Non-reaction is the conscious choice to pause and create a space of awareness before you respond.

- Example: Your partner makes a critical comment: “You never listen to me.” The ego’s instant reaction is, “Yes, I do! You’re the one who never listens!” Instead, you practice non-reaction. You feel the initial flash of anger or hurt arise within you, but you don’t act on it. You simply observe it. You take a conscious breath. You let the wave of emotion pass through you without becoming it. After a moment of silence, you can respond from a place of Presence, perhaps saying, “It hurts to hear that. What just happened that made you feel that way?”

2. Recognize the Pain-Body (in Yourself and Others)

Conflict is the pain-body’s favorite food. When an argument becomes intensely emotional and disproportionate to the situation, the pain-body has likely been activated. The key is to recognize it for what it is.

- Example: During a discussion about finances, your spouse suddenly brings up a painful event from years ago, and the conversation erupts into an intensely emotional, circular argument. Instead of getting pulled into the drama, you recognize internally, “Ah, this is the pain-body. This isn’t really him; it’s his pain speaking.” This recognition breaks your identification with the drama. You see that engaging with the pain-body is futile. You can then choose to disengage, saying, “This has become very painful. Let’s not talk about this while we are this upset.”

3. Feel Your Inner Body

The ego and pain-body are sustained by thought. One of the most direct ways to disengage from the mind is to bring your attention into your body. This anchors you firmly in the Now.

- Example: You are in a tense meeting with your boss, who is unfairly blaming you for a team mistake. Your mind is racing with defensive thoughts and angry rebuttals. In that moment, you consciously bring your attention away from your thoughts and into your body. Feel the aliveness in your hands. Feel your feet on the floor. Feel your breath moving in and out. This simple act short-circuits the egoic reaction. You become calm and centered. From this state of Presence, you can respond clearly and effectively, without emotional charge.

4. Practice Acceptance and Surrender

Surrender does not mean giving up or letting people walk all over you. It means accepting the is-ness of the present moment without internal resistance. You accept that, in this moment, the other person is saying what they are saying or feeling what they are feeling.

- Example: A friend is angry with you and is expressing their grievances. Instead of resisting their reality (“You have no right to feel that way!”), you practice acceptance. You listen fully without interruption. You can say, “I hear you. I understand that you are feeling angry and this is how you see the situation.” This act of non-resistance can miraculously dissolve the other person’s need to fight. Once they feel heard and their position is accepted as their position, a space opens for a more constructive, peaceful resolution.

By using these tools, you turn every conflict into an opportunity to awaken. You realize that your emotional success is not dependent on others changing their behavior, but on your ability to remain present, conscious, and rooted in the peace of the Now, no matter what happens on the outside.

Here are the primary intersection points of the four guides, with examples.

While originating from vastly different traditions—psychoanalysis, social psychology, Sufi mysticism, and modern spirituality—the guides based on Freud, Adler, Rumi, and Tolle converge on several profound concepts for achieving emotional success. Their language differs, but their core insights often point to the same fundamental truths about the human condition.

1. The Core Problem: The Unexamined “False Self”

All four philosophies agree that the primary source of emotional suffering and interpersonal conflict is a case of mistaken identity. We unconsciously identify with a limited, problematic part of ourselves and believe it to be the whole of who we are.

- Freud’s version is the internal battle where the rational Ego is hijacked by the primal drives of the Id or the harsh, shaming rules of the Superego.

- Adler’s version is the “mistaken lifestyle” driven by an unacknowledged feeling of inferiority, which causes us to strive for personal superiority rather than connection.

- Rumi’s version is the identification with the Ego (Nafs), the false self that thrives on separation, grievance, and being “right.”

- Tolle’s version is the identification with the Egoic Mind (the story of “me”) and its accumulation of past pain, the Pain-Body.

Intersection Concept: Emotional suffering is rooted in our unawareness of, and service to, a false or dysfunctional part of our own psyche.

- Example: You get a performance review at work that is mostly positive but contains one piece of constructive criticism.

- The “False Self” in all its forms latches onto the single negative point.

- Your Id/Pain-Body feels attacked and wants to lash out. Your Superego feels shame. Your Adlerian inferiority feels exposed. Your Rumi/Tolle Ego creates a story of being unappreciated.

- The result is a disproportionate emotional reaction. You ignore the 95% positive feedback and obsess over the 5% negative, creating internal turmoil and possibly leading to a defensive, conflict-ridden conversation with your manager.

2. The Solution: Shifting to a “True” or Healthier Self

Each guide proposes a path toward a more authentic, effective, and peaceful state of being, which involves a fundamental shift in identification.

- Freud’s goal is a strong Ego that can mediate reality, understand unconscious drives, and act rationally (“Where id was, there ego shall be”).

- Adler’s goal is to develop Social Interest (Gemeinschaftsgefühl), moving from self-centered goals to contributing to the common good.

- Rumi’s goal is to connect with the Heart or true Self, which is unified with universal Love and sees the divine in everyone.

- Tolle’s goal is to awaken to Presence or Awareness, the silent “Watcher” who is the witness of thought but not the thought itself.

Intersection Concept: Emotional success is achieved by consciously moving from a reactive, unconscious state to a more aware, rational, and connected state of being.

- Example: Following the same performance review scenario:

- Instead of reacting, you access the “Healthier Self.”

- Your Freudian strong Ego analyzes the feedback objectively. Your Adlerian Social Interest sees it as information to help you contribute more effectively to the team. Your Rumi-inspired Heart feels gratitude for the guidance. Your Tolle-inspired Presence simply observes the information without the mind creating a story of failure around it.

- You are able to thank your manager, ask clarifying questions, and use the feedback constructively, strengthening the relationship rather than damaging it.

3. The Universal Strategy: Observation and Creating Space

This is perhaps the most powerful and practical intersection. All four guides, in their own language, advocate for developing a form of “meta-awareness”—the ability to observe your internal state without being immediately consumed by it. This creates a crucial pause between stimulus and response.

- Freud’s entire psychoanalytic method is based on observing one’s own thoughts and history to find patterns. A strong Ego observes the Id’s impulse rather than just acting on it.

- Adler requires you to step back from a conflict to observe the underlying goal of the behavior, rather than just reacting to the surface behavior.

- Rumi’s “Guest House” metaphor is a direct instruction to observe your emotions as temporary visitors, not as you.

- Tolle’s core practice is to be the “Watcher” of your thoughts and feelings, creating a space of Presence.

Intersection Concept: The key to breaking free from destructive emotional patterns is to cultivate the ability to observe your own mind and emotions from a detached perspective.

- Example: A close friend says something careless that hurts your feelings.

- The Unconscious Reaction: You immediately lash out, saying something hurtful in return. The conflict escalates.

- Applying the Universal Strategy (Observation):

- The hurtful comment is made. You feel a surge of anger and pain.

- Instead of instantly reacting, you observe this internal surge. You think, “Ah, there is the anger. This is my pain-body activating. This is my ego feeling wounded. This is a feeling of inferiority.”

- This simple act of noticing creates a space. In that space, your healthier self (Strong Ego, Social Interest, Heart, Presence) can operate.

- Your response is now conscious, not reactive. You might say, “When you said that, it really hurt me,” or, “I need a moment before I respond.” This communicates your feeling without escalating the conflict, inviting connection rather than combat.

WE&P by:EZorrillaMc.

Google&GeminiSourced